Trust, digital health passes, equitable policy, and the U.S.

This post is an expansion of some thinking in Imagining a basic U.S. digital strategy for pandemics.

Context

The successes of nations such as New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan, Vietnam, South Korea, and China undoubtedly demonstrate the effectiveness of strong government intervention in controlling a virus as contagious as Covid. Basic, preventative measures such as mandatory traveller quarantine have allowed authorities to focus on domestic response while preventing new outbreaks introduced by travellers coming in from abroad. Proactive local and regional lockdowns physically stop outbreaks in their tracks, keeping infection numbers small, protecting the public and keeping hospitals from becoming overwhelmed even when testing might be limited. In taking proactive and cautious action, these nations have largely sidestepped all the effects of widespread and uncontrolled infection.

It’s rather clear that these control measures, even if implemented now, would be effective in substantially curtailing the spread of the virus in the U.S. It is low-tech, incredibly effective, and proven. However, for a wide variety of reasons, the U.S. and many other countries have made the conscious choice at the beginning of the initial outbreaks (and continue to make the choice today) to take the strong, proven measures off the table. While we may be holding it together just barely, this positioning is fragile; it is dependent on transmissibility and fatality rates being low enough that a certain number of infections and lost life is considered acceptable, it relies on vaccines as the exclusive method of combatting the virus, and assumes that mutations that increase transmissibility or fatality are limited.

The cost of this decision is undeniable – in the U.S. alone, it has come at the cost (at the time of writing) of 550,000 lives and countless medical complications. It has come at the cost of millions losing their jobs and the decimation of entire economic sectors. It has come at the cost of emptied bank accounts and exhausted families trying to hold it together as they balance work, childcare, and education.

Given the reality of the United States – a government (through both Republican and Democratic control) that is unwilling to impose (let alone enforce) strong quarantine procedures, limit/shut down domestic and international travel, enact regional or national lockdowns, or pass economic support to strained and hurting families – could there be a way to control a contagious virus like Covid in a “no-lockdown” country? How could we support “free” movement while allowing officials and health departments to contact trace effectively and notify people who might have been in contact with someone carrying the virus, instead of waiting for symptoms to arise? How could we transparently reduce “risk” at private businesses and between individuals, to support individual trust with the people around them?

The Core Issue

Let’s picture that the virus is much more infectious and fatal than it currently is. This is not to suggest that the severity of the current behaviour of Covid is “too low” – while I’d rather not suggest this hypothetical situation, the U.S. seems to have largely become complacent to the potential of contracting a virus like Covid and become numb to its death toll. Given this reality, could we collect enough information about the day-to-day behaviour of the population such that when it is all compiled together, it could give us an accurate picture illustrating the relative risk of each individual’s behaviour? With this data, could we, to a certain extent, provide some sort of certainty to individuals, businesses, and health officials around the risk of infection – and through enforcement, could we foster enough indirect trust between unrelated individuals that are in the same space such that “normal” life can be restored? Essentially, in a certain environment – say, an indoor restaurant – what would it take for me to trust that everyone around me is not infected or has had contact with someone with the virus? While it wouldn’t completely eliminate virus outbreaks, it could, with enough accuracy, be able to curtail the amount of outbreaks.

Without the ability to physically prevent infection through preventative measures like quarantine, any sort of “solution” in this reality would need to address every aspect of transmission and human behaviour – all this data is lagging, rather than leading – but if we can get as close to real-time as we can, there’s a potential to close that gap. Starting with the basic behaviour of any respiratory virus, some factors we would have to address:

- Viruses act in real time, 24/7 – any exposure at any time of day for any amount of time is a potential transmission

- Variable risk of infection – given it is a respiratory virus, the closer people are together and/or the larger the group, the higher the chance of transmission

- Virus transmission affects everyone – viruses have no ability to discern between race, socioeconomic status, environment, etc. Everyone should be considered a potential carrier of the virus.

Adding some basic factors on human behaviour when it comes to virus transmission we’d also have to address:

- Self-reported data is unreliable - Given the choice, it should be expected (esp. given a lot of selfishness during Covid in the U.S.) that people will lie about having potential exposure, their behaviour, or even known infection in order to live life “normally”

- Contact-tracing is only valuable when there are active efforts to contain the spread - Contact tracing’s usefulness is severely reduced when there is uncontrolled spread and/or a lack of effort from the population itself to contain the outbreak

- Restrictions must be equally imposed - it’s clear that the disparate state-by-state responses in the U.S. contributed to a muddy problem space that made it difficult for health officials in any state to argue for “more” or even maintain their current restrictions, as comparisons with states with fewer restrictions always made discussions on restrictions a race to the bottom. To avoid these sorts of issues, this effort would have to be equally applied.

A Solution

Keeping all these things in mind, whatever solution or set of solutions would have to, from a functional perspective:

- Always-active monitoring - Since virus transmission can take a little as a few seconds (in close contact) and is active all the time, data reporting frequency and reporting needs to be extremely high and automatic.

- Account for variable risk of infection - Since respiratory virus transmission is higher in denser, indoor, and closer-contact scenarios, data would have to account for these in order to avoid making overly-broad inaccurate conclusions (false positives) that reduce overall trust.

- Be used and enforced everywhere - If we imagine that this virus is much more fatal and infectious than Covid is in early 2021, and that this solution or tool is to be trusted at a national or international scale, accuracy is integral to its success. In the case of capturing behavioural information on who an individual might be in contact with, it would only ever be as accurate as its weakest link. No matter someone’s background, their job, their socio-economic conditions, or any excuse, its use would have to be mandatory to ensure the highest level of accuracy.

- Avoid self-reported data as a primary data source – it’s well-established that a self-reported data, especially when it comes to self-reported behaviour that has a social component, is unreliable. Data collection on behaviour, given the sheer amount of data points required when viruses transmit so quickly, is too vast to be self-reported either; this data collection should be automatic.

- Be accessible to all members of society – Any solution would need to be accessible to all people living in a nation, regardless of immigration status, ability or disability, technology literacy, or financial means. In this reality, accuracy must be ensured.

In my opinion, each of the five core considerations listed above are absolutely essential to a watertight “solution”; without any one of them, the entire solution fails. Any gap of time where we don’t know an individual’s status is a potential exposure. Too broad of an infection criteria, and public trust is strained, as the false positives outweigh any resultant restrictions experienced. Voluntary solutions diminish any collected data, as mass participation is integral to accuracy. Solutions reliant on self-reported data are too unreliable to really trust, given social pressure and individual desire to enjoy more “free” environments by providing inaccurate personal information. Inaccessibility to all members of society reduces participation, thus reducing accuracy.

With these requirements essentially mandated by the quirks of virus transmission and human behaviour, one promising “solution” to achieve this reality where we can gather, process, analyse, and communicate the data required for this data-backed community “trust” is a mandatory nationwide digital health pass: in simple terms, a national “Covid app”.

A National Digital Health Pass

A Vision for a Digital Health Pass

Let’s imagine that in early 2020 (or even now), the U.S. banded together and released a national Digital Health Pass (DHP) app. The U.S. develops this app to have one basic function: collect, evaluate, and communicate risk based on how close people are to each other. Using established technologies like Bluetooth LE, the app runs constantly in the background, pinging nearby phones (a proxy for a person) to evaluate potential contact – it’ll record duration, implied distance, and some unique ID for who this person might be, as anybody – even someone in their own household – is potentially infected. Using this data, the app can take these factors and create a variable risk profile for each interaction – high to low. It’ll do this all automatically, in the background.

An emergency order is enacted at a national level, requiring everybody to use the app to enter businesses, public transit, and governmental buildings. The app will display a coloured QR code, that is verified upon entrance to any public building. The QR code will be dynamic, preventing fraud. The scanner is also available in the app for personal use. A green QR code corresponds with low risk based on behaviour (frequency of contact, length of contact, location), yellow corresponds with medium-low risk, orange corresponds with medium risk, red with high risk. The criteria on how individuals are put into each risk category can be dynamically adapted based on the latest scientific understandings, via over-the-air updates. The point of this is to transparently manage an individual’s risk to the greater community; given this hypothetical reality where the virus is very contagious and fatal to the point it cannot be ignored, individuals with high “risk” profiles based on actual, recorded behaviour (e.g. a person has recently been in close contact with someone who has been found to be infected, regularly meets other people who are higher “risk” without social distancing, etc.) are not permitted to enter areas where the risk of transmission is high, such as indoor areas. Alternate, low transmission risk alternatives to businesses or governmental services would be required to be provided separate from “low risk” individuals1.

What this could provide is evidence-backed confidence at an individual and population level to “continue” life. While it doesn’t eliminate the need for basic virus-control measures such as physical distancing or masks, what it does provide (given enforcement) is trust between any two random individuals with a “low risk” status. If I, for example, can trust that everyone in some retail store is “low risk”, perhaps I’m more likely to patronise local businesses. If I invite a friend and/or their family over for dinner, I can essentially “protect” my family by verifying that their behaviour is “low risk” without asking uncomfortable questions about their personal behaviour that is inherently unreliable (differing understandings of “safe”, unreliable self-reporting, one-off “high-risk” behaviour). It could re-inspire confidence to take public transport, for risk-averse individuals to do necessary tasks like access government services that don’t have an online equivalent, for families to send children back to school2, and mitigate risk in communal living environments based on transmission events involving visitors, among many others.

Individual behaviour data would be anonymised wherever necessary, but signup would require individual identification3. Tying behaviour to an identity (even if only in a token verifying identity rather than the identity itself) to testing results (and eventually, vaccine status) could provide an even greater level of confidence within the population and could support efforts where people would need to be in sustained close contact with each other, such as hospitals or offices4. Testing and vaccine clearance via the app could support efforts to reduce transmission during travel (domestic air travel or inter-state road/rail travel) while mitigating the risk of re-introducing the virus to communities where virus incidence is low, thus avoiding virus “spikes” that result in mass death events. Individual interactions that contribute to someone’s virus risk profile could be “cleared” by testing results or vaccines, especially for those who work in higher-risk environments out of necessity.

From the perspective of a local, state, or national public health expert or policymaker, this data could be used to address potential outbreaks as they happen, rather than waiting out the entire incubation period (e.g. Covid’s 2-week incubation period) and relying on lagging indicators like reported symptoms. It could be used to target testing in a way that can provide certainty about different types of events or investigate the likeliness of a potential mass transmission event. It would make contact-tracing automatic and digital, allowing seamless, up-to-date notifications at an individual level about potential exposure, and steer them towards testing. It could provide concrete, data-driven context to inform re-opening policies. With testing results and vaccine status, it could provide an extremely accurate picture of novel virus behaviour in the wild at a population level, a step-change for research.

Eventually, through national policies, vaccine and testing systems would be made interoperable with the DHP, allowing easy access to testing results and vaccine status without the need to chase down medical information on paper or through the myriad of electronic medical records systems. It would simply be linked to your identifier, and be accessible at your fingertips.

In its ideal end state, the DHP app becomes a platform for population health data and functions as an arm of public health institutions during the pandemic. Rather than public health policy being limited to fragmented efforts across thousands of different jurisdictions, the app becomes the face of a national virus-fighting strategy, and can encompass:

- public health education at a national scale, a monumental shift in public health information strategy5

- fully-leveraged digital contact tracing (beyond just anonymous exposure notifications)

- access control to limit spread / introduction of mutated strains and prevent mass death events

- empowerment of individuals to check others’ status and reduce spread

- easily-accessible, centralised, and verified testing and vaccine statuses; a “vaccine passport”

- provide data to inform strategy and equitable policy

This is just the start. There are undoubtedly many more uses of this data that I have not outlined, ideas from people much smarter than I am. This basic framework is not technologically out of reach; nor would it take particularly long to develop. It could run on standard server hardware and leverage the already-powerful computers that the vast majority of Americans carry everywhere every day. While there a number of critiques regarding political feasibility and issues around equity and access (that I explore in Addressing Critiques), this reality is possible. It’s quite obvious that it would be a lot simpler to just use mandatory quarantines, lockdowns, and limit travel to avoid the outbreaks in the first place – but even so, I think it’s valuable to explore these ideas, given that “uncontrolled spread and death until we can vaccinate you” seems to be the unofficial virus mitigation strategy of the United States.

Learning from other approaches

Exposure Notification Apps

In the United States, it’s difficult to argue that the Exposure Notification System apps, developed independently on a state-by-state basis, can be seen as a success. While I am sure it has been helpful in notifying some people of potential exposure with some success, these apps have never been set up for success from the very moment they were released.

The Exposure Notification Systems (ENS) functions – at a core level – exactly how we want it to: it uses technology (Bluetooth Low Energy) to record who (via entirely anonymous identifiers) and for how long some individual has contact with others. If we could use this data to its fullest extent, it could be the basis for our ideal DHP – but in practice, it has not.

ENSs as built today can largely be considered ineffective for a number of reasons: participation is opt-in/optional, use is not enforced, the data accounts very little for inter-state or international travel, and relies on self-reported data. As of March 2021, there are only 23 states (incl. DC) that even have ENS implementations6, further driving down the effectiveness of these systems at a national scale. While the 23 individual implementations of the ENS app all technically all interoperable7 (e.g. New York’s version technically works in California, as they all operate on the National Key Server run by the APHL), they are marketed and treated as applicable only to the state released the ENS app. Add to this that each state implementation is named differently, making it difficult for people to “switch” to another ENS app when they travel to another state8.

It’s clear that data on potential exposures is really only effective when the vast majority of the population participates. Without mandatory mass participation and up-to-date statuses on infection, the effects of these apps are marginal at best. In Washington state (the first state with confirmed Covid cases), for example, there have been 1.85 million total downloads9 of the “WA Notify” ENS as of March 2021 against a total population of 7.6 million; roughly, a 25% compliance rate. It’s hard to argue that, in a normal situation such as going to the grocery store, having 75% of the people there not providing information about their recent potential exposures makes a large difference. Even for those who are found to be positive for infection, sharing that positive result is optional (and in some cases, must be pre-verified by the state health authority10 before sharing that result with recent anonymous contacts through these ENS apps).

In a best-case scenario, someone in Washington or California in March 2021 (where use of the ENSs is highest in the US) would be notified of a potential exposure to the virus only if they AND the person who got a positive Covid result were both using the app (~30% x ~30%, so less than 10% total chance at random), the Covid-positive person reporting that information via the app of their own accord (likely, 50% at best), a chance further diminished by low awareness of this in-app functionality, potential hospitalisation due to the virus, and even factors such as inaccessibility due to language barriers or disability. Factor in the fact that only 23 of 51 US states (incl. DC) even have these systems in place, and our best-case scenario is that 2 or 3 of every 100 Covid cases in the U.S. ever being assisted by the current application of an ENS as built.

It’s easy to see how effective the ENS approach could have been: an anonymous (albeit limited) system automatically notifying people of potential exposure. But relying on voluntary participation (not enforced or made mandatory), high barriers to simply reporting a virus-positive status, low public awareness of the tool, and not even half of all states even participating in the program almost a year into the Covid pandemic has doomed the program to marginal utility since the beginning.

Vaccine Passports

“Vaccine Passports” address a single issue: how do you verify that someone has been vaccinated to prevent infection at a large scale? Functionally, it’s a glorified vaccine card, tied to an identity, and resistant to fraud. While the American media and public appear to be rather hesitant11 to the idea of vaccine passports, the idea is gaining traction outside the U.S., especially as countries who have controlled Covid consider re-opening their borders. True to their name, vaccine passports are credentials (a verified vaccine status, tied to an identity) backed by an authority (a country, for example) that can be checked to permit entrance into some space – a venue, an airplane, a nation.

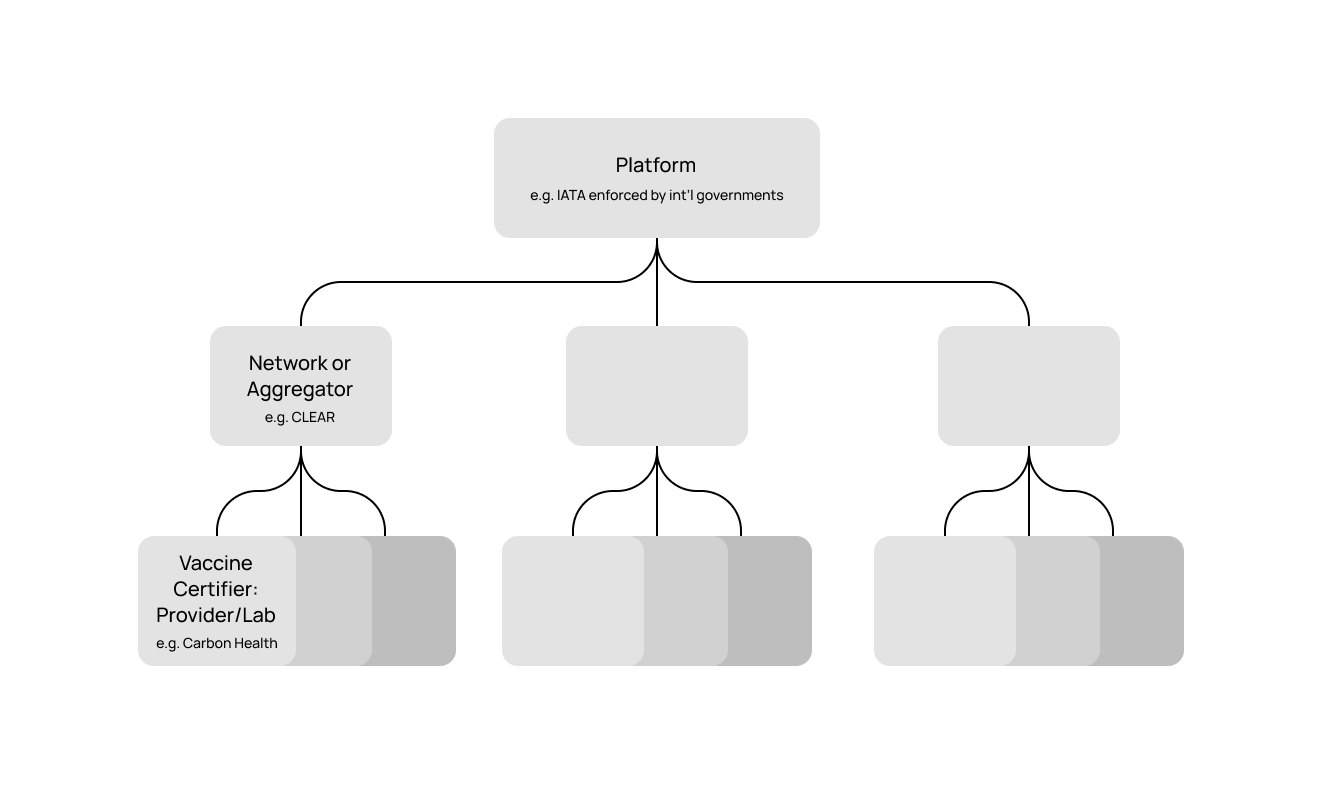

While they don’t attempt to solve everything our theoretical DHP does, the success of vaccine passports as a whole are dependent on a lot of the same core factors that we have explored. Since vaccine passports deal with a post-vaccination reality, the factors which address pre-vaccination scenarios – always-on monitoring and accounting for variable infection – are less of a concern. However, the remaining three factors are still integral to the success of any vaccine passport: mandatory use (and its enforcement), the avoidance/elimination of self-reported data, and accessibility regardless of financial means. To illustrate this, I think it’s useful to look at three current approaches: Carbon Health’s “Health Pass”, CLEAR’s “Health Pass+”, and the IATA’s (International Air Transit Association) “Travel Pass Initiative”.

Each of these approaches has their own app, all of which look and function remarkably similarly: some sort of identity verification, some sort of dynamic QR code, a slick app for users to display their vaccine status or testing information. Interestingly, while each of these public-facing user interfaces look and function similarly, how each contributes to a future where the public at large can verify their statuses varies wildly.

Carbon Health, a healthcare technology company that operates clinics, laboratory testing, and telehealth services, also operates an app for their patients; a proprietary, portable electronic health record. This is perfectly suitable for day-to-day patient-provider relationships, especially in the boutique setting that Carbon Health operates in. While Carbon Health can independently certify that a vaccine has been provided to a specific user and display that in their app, Carbon Health’s limited size, both in terms of providers/testers and patients (they only operate 27 clinics across 6 states)12, results in an app that can only ever be as pervasive as their practice.

CLEAR (the same company that allows you to skip the TSA PreCheck line at major airports with a premium annual membership) has also introduced an app, called “Health Pass+”. Like Carbon Health, they have a proprietary app; however, unlike CH, CLEAR is not a provider. CLEAR primarily aggregates data from various sources (in terms of testing, they report working with up to 30,000 labs13, but their integrations with hospitals, providers, or health insurance companies to verify vaccines, given those companies even record such data, is unclear). Strategically, if CLEAR, a private company aggregating identity information, can leverage their existing partnerships (TSA, airlines, and sport franchises), they do have the potential of being the de-facto identity and vaccine verification authority – however, they undoubtedly have an uphill battle when it comes to integrating with the thousands of individual clinics, hospitals, insurance companies, and health districts (through individual B2B contracts).

Personally, the IATA’s (International Air Transport Association) approach is the most interesting. A trade association encompassing many of the world’s largest airlines, the IATA has proposed their “Health Pass Initiative”, a global and standardised framework to support “country regulations regarding COVID-19 passenger travel requirements”14, with a “Travel Pass” app as its public-facing product. Essentially, the IATA’s HPI functions as a translation layer for international Covid regulation compliance – allowing Country A to verify the status of a traveller from Country B through standardised verification. While the proposed user interface is functionally extremely similar to those of CLEAR and Carbon Health, the theoretical effectiveness of the IATA HPI is much higher – enforcement is guaranteed by a binary governmental decision (allowed entrance or not), compliance and participation by airlines to support travel broadly (in their own self interest, which supports public health and consumer confidence), and an effort that does not have an underlying profit motive (at least by the IATA). Backed by the authority of the governments of nations who participate, enforced by the self-interest of enhanced consumer confidence by the airlines themselves and border officers, and compliance across the industry via the IATA, the IATA HPI is one approach that can potentially succeed.

Dialling back to our three core factors for vaccine passport success, we can see that even though approaches such as those by Carbon Health, CLEAR, and IATA all have similar public-facing health pass apps to address Covid, their theoretical successes depend largely on structural factors. All three approaches address the issue of self-reported data: providers like Carbon Health can directly authenticate vaccines, while CLEAR and IATA take more of an aggregator type role (each of these approaches is dependent on the integrity of the data that is passed to these networks. IATA can potentially enjoy a government-backed integrity status, which gives it an upper hand). Regarding mandatory use that would markedly improve the response to virus transmission, Carbon Health and CLEAR suffer: each of these approaches require B2B partnerships, contracts, and enforcement to even approach ubiquity; IATA does not. On accessibility with regard to financial means, all of these vaccine approaches are lacklustre. Carbon Health is limited to its small and premium private network, CLEAR by its limited partnerships and orientation as a premium identity provider especially through its cost-prohibitive $179/yr CLEAR membership, and IATA by the accessibility of international air travel.

IATA’s approach appears to be the most promising of the different types of vaccine passports: mandatory use and enforcement backed by international governments and airlines, data integrity backed by governments (in their best interest for international relations and public image), and a somewhat accessible app (though limited to international air travel) that does not require membership in a specific network or provider. Carbon Health and CLEAR are successful in their own limited spheres, but are more indicative of the U.S.’s current future without a centralised DHP – a crowded marketplace of non-interoperable privately-run “vaccination passport” apps.

Addressing Critiques

Equity and Universal Access

In a lot of existing writing15 on vaccine passports and digital health passes, the concept of equity and universal access is often applied to these ideas critically; a good perspective to have. However, while applied critically, the concept of equity and universal access is also applied dismissively: ideas around how these products could be applied equitably and be accessible universally are not explored in the slightest. In this, I’d like to explore: how would we actually ensure that a DHP was universally accessible and supports equity?

Universal Access

In our pursuit for the ubiquity of this DHP, smartphones offer the easiest and fastest way to get the functionality into the public’s hands. According to a survey16 conducted by Pew Research, about 80% of adults in the United States own a smartphone, leaving about 20% of the adult population not able to participate in the app-based DHP. One way to address this issue and ensure that as many adults have access to the DHP (and the informational resources around the virus that could be delivered via smartphone) would be to directly subsidise the cost of smartphones (preloaded with the DHP) targeted at underserved communities who are less likely to own smartphones: generally, people who are above the age of 50, in more rural areas, and/or lower income16. To encourage full participation among those who already have smartphones and to ensure that public health information can have the widest impact and is accessible, a portion of monthly data charges could be subsidised as well and data associated with government sites could be zero-rated. This would have a knock-on effect of directly supporting access for individuals and families who are lower-income or homeless, and broadly lowering the financial barrier associated with digital access for the entire U.S. population. There are also other approaches: for those who struggle with the complexity of smartphones, Bluetooth-enabled feature phones or simple pager-like custom devices could be designed and manufactured en masse to achieve similar effects, accessible exclusively via older 2G networks rather than modern 3G/4G/5G networks. While the cost associated with such a program would be high, it would have certainly be but a fraction of the several trillion dollars already associated with purely preventing American economic collapse in 2020, and would have the beneficial effect of digitising a large swath of the American public. If we budgeted $400 per American (regardless of age) for the blended cost of devices, subsidies, and capital expenditures associated with bringing wireless technologies to areas which need them, we would be looking at a total cost of less than $150 billion, a steal in comparison to the $3 trillion+ allocated to backstop banks in 2020 alone.

Steps would be taken to ensure accessibility for those experiencing disability, such as difficulty seeing or hearing. VoiceOver/TalkBack and other assistive technologies would be built in by default, and careful consideration applied to the structure and use of the app to account for use-cases such as in-home care providers. All user interfaces or other information would have translations and be written without jargon to ensure accessibility. Considerations around privacy and identity could be built in to ensure that those without legal status would also feel comfortable using the DHP as a public health tool: the virus does not discriminate based on legal status. The goal of the DHP would be public health above all else, a goal achieved only only through full participation.

For the small portion of the population that would not be covered by these wide expansions of digital access – the last couple of percent – information could be delivered in more traditional manners: paper information packets, paper vaccine cards, paper testing results. In this world, the participation of the vast majority of the population would hopefully be enough to protect the few who do not have the ability to jump through the public health hoops; however, as the integrity of the data is of utmost importance to the DHP, these cases should be kept extremely limited, as the abuse of the “trust” created by mass participation by those who do not need it compromises the public health efforts for all.

Equity

In addition to exploring the issues of equity in access to the DHP outlined in Universal Access, it’s also important to explore issues that might arise from the application of the DHP.

The most obvious of these issues is access control: the notion that we can enforce restrictions on who can be let into a space or who is kept out, and the potential issue that essential workers such as grocery store clerks, customer service, food service, or labour-intensive jobs such as construction, would be effectively be “punished” for doing a necessary job that is “higher risk” by nature and unable to access the same resources as those who are able to minimise their risk by choice. This is a fair critique. However, there are opportunities to support the implementation of public health-protecting access control with equitable policy.

One potential solution is to prioritise certain types of resources for certain virus risk statuses; those with high risk (whether it be via their job or some one-off circumstance) of transmission are prioritised for contactless services; for example, an ICU nurse might enjoy the most preferable “contactless” grocery pickup times, while a normal “low” risk person might have a wider pickup time or be pushed to the next day. This might also extend to other resources like governmental offices (e.g. DMV) or even immediate purchase access to a reserved stock of high quality PPE; helping to alleviate some issues that we’ve seen where individuals and families with means might hoard an excess amount of life-saving resources but might not necessarily need them, focusing allocation and access to those who need them the most.

When testing is limited, the resources can be prioritised to those with higher risk as well. While it’s important that people with no symptoms get tested regularly, testing can be prioritised based on risk, ensuring that the testing effectiveness can be maximised. When a vaccine is also available but limited, historical data can also provide insight into the need, ensuring that vaccines are allocated where they are needed and not fraudulently accessed. This data might also be helpful in ensuring further equity in vaccine distribution for occupations or higher-risk environments that might not be “officially” listed in prioritised vaccine rollouts, but still might meet the threshold for earlier access to the vaccine.

The isolated argument that there are equity issues in restricting access based on “potential risk” is, without a doubt, valid. Given the current reality and a priority of avoiding mass death or mass infection, I believe that there are approaches like the prioritisation of other resources, that could holistically support a broadly equitable approach. Admittedly, it’s not perfect, but possible without significant deviation from the current (neoliberal) reality.

This exploration does not address every issue of inequity that might arise from this DHP-based approach, but I hope it does open the door to good-faith exploration of holistically equitable approaches that can move us forward and avoid dismissive critiques of “equity” the lack a substantive exploration of the core ideas.

Privacy (and China)

Like equity, privacy is a topic that existing literature seems to throw around a lot without actually exploring any solutions or potential mitigation strategies. The current discourse around “privacy” in the United States is focused on a uniquely American perspective, emphasising an absolute and individualistic conception of privacy: i.e., my data is mine and mine alone, no matter how useful it might be if aggregated for the public good.

Hand-in-hand with U.S. anti-communist rhetoric (often, anti-China foreign policy projection) that contrasts the “freedom” in the United States with the “lack of privacy” abroad and the spectre of “Big Brother”, most American commentary on potential DHPs or even more basic ideas such as digital vaccine passports defers to this concept of absolute privacy as one of the main reasons why vaccine passports are not possible in the United States. The core argument that I have seen time and time again against the idea of government-run digital tools over the last twelve months has been: “we’re not China, they have no freedom, and therefore tracking apps are impossible”. Ironically, despite the heavy-handed rhetoric against stronger measures such as universal lockdowns and Covid apps, these initially untenable ideas have gained significant public traction, to the point where calls for full lockdowns are common on Twitter and vaccine passports are being actively explored by the Biden Administration – an indirect acknowledgement that the “privacy” issues that were originally portrayed as so abhorrent to American values actually were exaggerated all along. This is not to suggest that authoritarian surveillance is “good” by any stretch of the imagination, but to recognise that a significant portion of the Stateside “privacy” rhetoric was more of a projection of U.S. foreign policy and political talking points than it ever was a substantive exploration of its merits.

Setting the rhetoric aside, however, there are ways we can achieve a reasonable implementation of “privacy” in service of a functional and useful DHP. This “privacy” cannot be a sort of extreme crypto-utopian, completely anonymous, and fully decentralised system, but rather, a good-faith effort at preventing centralised data systems that tied to individual identification from being abused by whoever happens to be in charge of or have access to the system. There is also the core element of implied trust as a core tenet of the DHP: completely anonymous systems often fail to create ad-hoc trust because it lacks the somewhat natural accountability that comes with being identifiable. We can then ask: what does a system that can support valuable public health decision-making, support a public perception of accountability for personal actions or behaviour (in respect to virus transmission alone), but also protects individuals from the leakage, exposure, or abuse of PI (personally information) from those with institutional power (e.g. governments who might use it for undesirable non-public health purposes, e.g. immigration enforcement, crackdowns on dissenters, etc.) or hackers look like?

For the ‘contact-tracing’ and ‘risk mitigation’ portion of the DHP (let’s assume that vaccines are not viable yet), direct individual identification is not actually necessary – however, ensuring that only one person can ever have one instance of the DHP is important to ensure integrity of the system as a whole by preventing inaccurate/fraudulent data (e.g. somebody using multiple phones or regularly resetting). In essence, the identity of the user does not matter as much as the value of the verification of their identity.

This could be achieved by keeping identity verification completely separate from the DHP itself. Users would generate a functionally anonymous identifier (e.g., a cryptographic fingerprint / checksum) by supplying some verification of their identity (for those with legal status, this could be a combination of government ID combined with public records; for those without legal status, it could be just their national ID) to be used with the DHP. In this manner, as the systems are kept separate and the identifiers themselves cannot be reverse-engineered, no PI actually needs to be stored by the DHP for a user. However we can reasonably ensure that only one person is ever associated to one identifier and mitigate the potential hazard of the leakage of PI by never storing it in the first place (and ensuring it cannot be reverse-engineered by bad actors).

Using this functionally-anonymous, generated identifier as the only identifier in the DHP data would resolve a lot of immediate privacy issues that are concerned with having DHP data directly associated with PI. Eventually, this generated identifier could also be used in the process of ensuring that testing results or vaccine results are linked to a specific identity through tokenisation, avoiding any PI from actually needing to be transmitted.

Ideally, this system would be centralised. While it would of course be more private to only store contacts locally and only expose the relevant data if directly requested by some immediate exposure event (like how the ENSs currently work), I think this limits the true value of the data. Especially if combined with optional self-reported data like occupation and demographic information, this data could be incredibly insightful at a population level to really understand the behaviour of the virus itself, helping to shape and support equitable and effective public health policy or decisions. From an automatic contact-tracing standpoint, contacts could be traced or notified at a second (or more) level beyond people immediately exposed to a transmission event, helping to move public health responses with respect to these viruses from more of an observational and “reactive” approach to one that is preventative. Researchers could have access to this anonymised data, producing insights that could be dynamically integrated into public health policy. Across all of this, a standard deletion policy could apply (for example, double the period where someone is typically contagious), keeping the data focused on serving the current needs and avoiding risks and potential long-term issues with extended data storage.

To ensure that the systems are used only for public health purposes and support public image of the DHP, the DHP framework itself could be made transparent, at the very minimum to third-party auditors. Access to any of the raw data (other than for verifying identity for test results/vaccines etc.) would be recorded and kept strictly to public health officials and academic researchers. An executive order could be written codifying these limits, preventing use by other agencies (e.g. DHS, ICE, etc.) and limiting direct abuse by government in any sense. Broadly, mitigating issues around privacy are just as much a legislation-backed public messaging effort as they are a technical effort: the trust is essential.

This approach is not perfect, not do I claim it is. However, as of March 2021, I find it ironic that despite the constant public commentary around undefined ideas of “equity” and “privacy”, the current approaches all seem to lack any sort of structural acknowledgement of these issues. Instead of thoughtful policy, we in the United States now face a future where vaccine verification in the next twelve months will likely be dominated not by a single public provider with thoughtful policy (even as limited as this exploration), but instead by opportunistic companies all vying for a slice of the “vaccine passport” – and by extension, the digital identity provider – market. All these companies in our current future will realistically be backed by opportunistic VCs, insurance companies, health networks, and data analytics contractors. To a typical American, this will inevitably manifest itself in an entire screen on their phones for the seventeen “vaccine passport” apps used across all the places they want to visit regularly. I find it hard to even entertain the argument that every one of these privately-motivated companies will ever hold privacy and equity to the same standard as a public and transparent system. In the search of dogmatic and vague conceptualisations of privacy and equity, we’ve allowed the exact opposite to creep up on us and become our reality.

Closing Notes

There are undoubtedly countless caveats and issues that I am sure I have overlooked (and would love to hear about!). This is just one exploration of how things might be done, from the limited perspective of a digital designer.

Personally, it’s hard not to see the critical but dismissive portrayal of Covid apps and vaccine passports in influential national publications and newspapers over the last twelve months as anything but a delay towards this inevitable future. Combined with the delays that came with the fetishistic maintenance of vague yet idealised versions of “freedom” and “privacy”, we’ve rejected every idea that didn’t meet these ideals, to the point where the exact opposite – vaccine apps run by private companies – have become our reality. Despite all their issues, digital vaccine passports have always been the logical end to a pandemic, and in our stubbornness, have paid the price for these sad intellectual exercises: five hundred and fifty thousand people dead.

However, I feel these seven thousand words are overall a critical but good-faith and optimistic attempt to examine the mistakes we’ve made as a nation and propose how we might approach a more equitable, accessible, effective, and life-saving digital health pass. That future is possible, and I hope this piece adds a perspective and fresh eyes to the Covid reality that we so desperately want to be done with.

-

I understand there are obvious equity issues with this approach – poorer folks, persons of colour, and other marginalised communities are more likely to work or live in environments that inherently puts them at higher risk such as high-traffic areas and communal living environments. No approach is perfect, and I believe this can be balanced equitably (and I explore this, in this piece) through preferential treatment in other aspects such as earlier access to vaccines, accelerated services due to “essential worker” status, etc. The core question this approach attempts to solve, however, is the common yet misleadingly simple question of: how do you balance individual “freedom” with the risk of community infection? In essence, is it “fair” to individuals and families who exhibit “safer” behaviour to have to risk their health by forcing them to be in the same spaces as individuals and families who are known to not? I explore these ideas in the EQUITY section of this piece. ↩

-

This is only possible in the case where it is known and proven that children are much less likely to transmit the virus. ↩

-

In the American context, there are obviously issues here around the public conception of privacy and HIPAA. I explore these ideas in the PRIVACY section of this piece. ↩

-

Only when being co-located is actually necessary, e.g. blue-collar work generally. ↩

-

See Imagining a basic U.S. digital strategy for pandemics, or other writing like Ro Khanna and Shaun Modi’s The US Government Needs to Invest in Digital Design ↩

-

Retrieved Mar 20, 2021 from Android Police ↩

-

See the APHL’s National Key Server: ↩

-

The process in “switching” between different state implementations of the ENS apps (e.g. New York’s “COVID Alert NY” and Washington’s “WA Notify”) is slightly easier on iOS as it is managed on a system level, but still requires an explicit switch, which I am sure sees very little use. It’s bizarre that they’re treated and developed as independent entities yet are actually interoperable, but not marketed so. ↩

-

Retrieved Mar 20, 2021 from WA Department of Health. ↩

-

One example, in Washington State as of March 2021 from wa.gov: “If you test positive and public health reaches out to you, they will ask if you are using WA Notify. If you are, they will generate a verification code and help you enter it into WA Notify. The code is not tied to your personal information. Public health has no way to know who will be notified by the app about exposure when you enter your code. The notification will not include any information about you. The more people who share their codes, the better we can prevent the spread of COVID-19.” ↩

-

“In Coronavirus Fight, China Gives Citizen a Color Code, with Red Flags”, New York Times 03/01/2020 “Virus-Tracing Apps Are Rife With Problems. Governments Are Rushing to Fix Them”, New York Times, 07/08/2020 “Expert: Vaccination Passports Could Become a “Dystopian Nightmare”, Futurism 03/02/2021 ↩

-

Retrieved May 20, 2021 from TechCrunch ↩

-

“Vaccinated? Show Us Your App”, New York Times, 12/13/2021 “Vaccine Passports Can Help the US Reopen – or Further Divide Us”, WIRED, 03/02/2021 ↩

-

Retrieved March 22 from Pew Research ↩ ↩2